Cynthia Madansky - Always Avant Garde | S5 E09

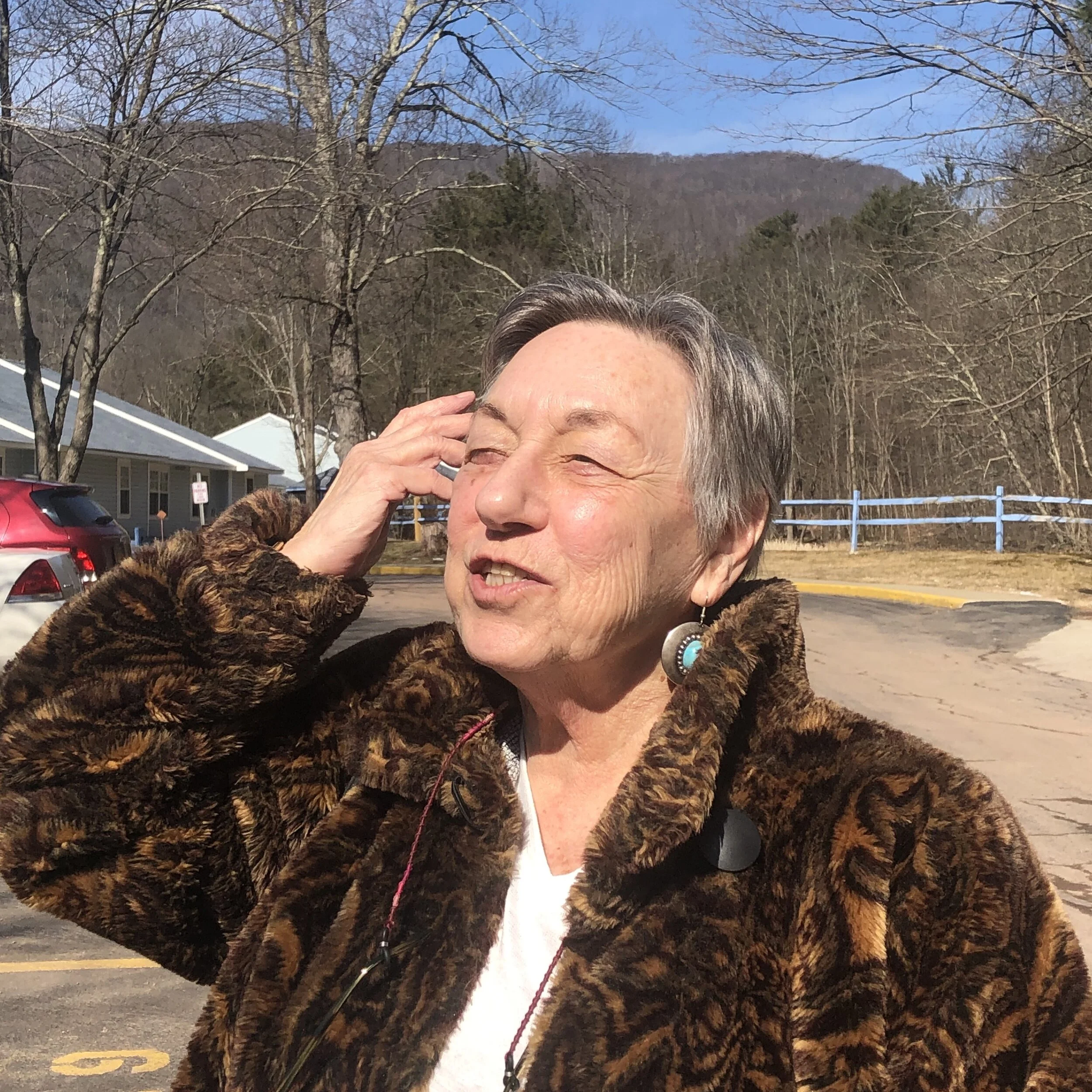

Cynthia Madansky, 58, describes herself as a Jewish, queer filmmaker and artist. For TOB, she embodies what it means to live a creative life.

The recognition she has received – a Fulbright, a Guggenheim, the Rome Prize and so much more – has not altered her commitment to a minimalist life where her art always comes first. She follows her curiosity, her politics, her aesthetic voice and her instincts to create award-winning films that are impossible to categorize. They are not documentaries, they are not narratives: they are deeply beautiful, reflective and political. Her bold and creative genius extends to her own life, with frequent re-locations and explorations while living in Turkey, Palestine, Russia, and Italy, and a commitment to always returning to New York City.

We caught up with her soon after she came back from living in St. Petersburg Russia, working on her last film entitled ESFIR. She is now in pre-production, planning and fundraising for her next great opus: a film that will portray the nuclear landscape in all 50 states and US territories.

Check out Cynthia’s paintings, films and travels at: http://madansky.com

+ TRANSCRIPT

Idelisse & Joanne: Welcome to Two Old Bitches, I’m Idelisse Malavé,

And I’m Joanne Sandler, and we are two old bitches!

We are interviewing our women friends, and women who could be our friends. Listen as they share stories about how they reinvent themselves!

Joanne Sandler : Hi, Idelisse Malavé!

Idelisse Malavé: Hi Joanne !

Joanne Sandler: So this episode, episode nine

Idelisse Malavé: Fabulous episode!

Joanne Sandler: absolutely… is with a woman who I've been friends with for more than 30 years, whose name is Cynthia Madansky who is an extraordinary and impossible to categorize filmmaker

Idelisse Malavé: And a painter

Joanne Sandler: And a painter and an artist, an artist in every bone of her body.

Idelisse Malavé: And I have just, I just met her last couple of years when we went to Istanbul for work. I met her there. We had dinner with her while we were there. And this, this conversation with Cynthia was this- for me, a compelling and exciting event, to really be able to talk to an artist of her caliber about her process and what drives her and how she makes these incredible films that you were saying earlier. So aptly, I think that are impossible to categorize if they don't fit neatly into any particular-

Joanne Sandler: They don't! they're- they're kind of documentary, but they certainly don't fit into a documentary category. They're not experimental. She calls them avant-garde; they are very political.

Idelisse Malavé: She sometimes says it's like an essay. Exactly. She says for the most part, they don't have a beginning, middle and an end. Right.

Joanne Sandler: And since I've known Cynthia and watched over the years, as she has really built an incredible catalog of, of work, you know, the thing about Cynthia, because she creates really from her politics and her drive to say something about the world is that unlike a lot of other filmmakers, she, her output is huge. And you made the point while we were talking to her that it's actually hard to find a place online where you can see her work

Idelisse Malavé: because like many true artists, filmmaker, artists, she wants for the audience to be in a place Where they're actually, whether it's a cinema or a museum where they're actually engaging with the work. And not as I think she says in, in our conversation, you know, put it on pause while they go get a drink of water or go to the bathroom. Right. She wants folks immersed in the experience. Yeah.

Joanne Sandler: And so, the thing is that Cynthia has been recognized many times for her work. She's won the Rome prize. She got a Guggenheim, she got a Fulbright. I mean, she has received a fair amount of recognition for her work and still as an artist. And she talks about this, you know, how do you survive as an artist, Sharon Louden, who we interviewed many episodes ago now talks about the same thing; How do you build a sustainable life as an artist? And it's so interesting to see Cynthia at 58 years old, right? Having- been doing this for decades.

Idelisse Malavé: Particularly for filmmakers, you know, for a painter, which Cynthia is also a painter. The costs of painting are so small compared to the cost of filmmaking, right? with the budget is, is you really need to be able to tap in and draw on resources, outside resources. So that energy has to, has to go in that direction of tapping into those resources.

Joanne Sandler: And so we started this episode by asking her, as we usually do, who is she?

Cynthia Madansky: I’m a 58 year old, Jewish queer filmmaker artist. Identity.

Joanne Sandler: That's your identity? Does that like come easily?

Cynthia Madansky: Definitely. Absolutely.

Joanne Sandler: How do you choose?

Cynthia Madansky: I think Jewish is first.

Joanne Sandler: Why?

Cynthia Madansky: Because there's so much in visibility about being Jewish and you always are seen as like this, you know, Christian White girl, which you're not. And also I think age at this point is really essential and important because 58 is close to 60 and that means, wow, you know, I've, you know, I'm an older woman now. I'm not a 30 year old or a 40 year old even, or 50 year old. I'm like going to be a 60 year old. So it's a really different position in the world to be an old woman with, you know, older woman with gray hair. You walk around the world.

Idelisse Malavé: You corrected yourself, first you said old, and then-. What's the difference between saying older woman and old woman?

Cynthia Madansky: I don't feel old. I feel like I'm 17. I definitely, I mean, I still feel my spirit is very young. So I just know in terms of years, I have the years, but my Spirit's very young, so I'm older in terms of age, but I'm not old. I'm not old at all.

Old to me. It's not-- It's not that you're not creative or you're not productive, but that you have a different perspective on the need to produce so much. And I think that at some point I-

Idelisse Malavé: So, old is not generative in your mind

Cynthia Madansky: No, it's, it's not a negative thing. It's just like, I've done enough. Like I can just sit and read all day or I can take walks or I can visit friends and not be like, oh my God, I have to go work. Like, to me, it's like a blessing. Like you can have, you can just take walks in nature and be with your friends and you don't have to like, oh my god I have to produce this. And if I don't, I can't sleep

Joanne Sandler: chill, So old is chill to you.

Cynthia Madansky: Old is chill!

I think it changed radically when I was making 1+8 with Angelika Brudniak. And we were making a film at the borders of Turkey

Idelisse Malavé: Say something because Joanne knows more about your filmmaking than I do. Obviously. What is 1+8?

Cynthia Madansky: 1+8 is a film that was completed in 2011- 2012. And it's a portrait film of the borders of Turkey. So, we went to border towns and Turkey, Syria, Iran, and-

Idelisse Malavé: But a whole bunch of them, right? How many?

Cynthia Madansky: There's eight borders. So Turkey it's 16 border locations. We spent about a month in each border, in each border town. And what we found was that there was an openness of people from all ages to speak with us because we were older women and also probably older foreign women. We weren’t Turkish and we weren't- you know, we were foreigners. She's Austrian I’m American. And I think because we were older, we did not have any issues of harassment that younger women would have had in the border. We stayed in brothels because basically in border towns, there are no hotels. So there are only brothels. So I think our presence as older women really gave us access to quite a lot now. also respected, we had respect. young people, older people didn't matter, queer, straight, radical, not radical people, respected us because of our age.

Idelisse Malavé: We had an opportunity to hear just now about two of Cynthia's five facets of her personality, her age and her Jewishness. But we wanted to hear about her queerness.

Cynthia Madansky: As a 58 year old woman, who's traveling and making films. You're already different because most women who are 58 have kids and grandkids and husbands and or they have their lesbian lovers and their kids and their grandkids. So, already you're outside. You're a little bit different. So I don't think it translates in terms of necessarily sexuality. Oh, she's heterosexual or she's a lesbian, or it's more of a, it's kind of a disposition in the world. And an openness, I guess, queer for me is an openness.

Joanne Sandler: Actually loved this part of the, of our conversation with Cynthia, Ide, because it's where she starts to kind of pry open this, this point about why does she creates so much work that is so hard to find

Idelisse Malavé: Well and- and talks about how important the relationship with the viewer is to her.

Cynthia Madansky: I really want to screen them in cinemas and they’re films and they need to, you know, how people watch movies right now. It's like, oh, get up and have coffee and we'll go to the bathroom. And I want it to be an experience in a cinema. So unless you're a program or unless you're saying, yes, I know you, and yes, I'm going to watch it. I'm not going – of course I can't control if you take breaks or not, but I really want more engagement and it's not because I'm making money on my films and that's why I'm not showing them. It's just more about a relationship I want people to have with the work itself. So if you wrote to me and said, I want to watch these films, I would say, okay, here's the link!

Cynthia Madansky: I studied art in Jerusalem at Bezalel and I was a painter. I got into the art department and there was a video class and I started making films, but I was so attached to being a painter.. I was like, yeah, like filmmaking.

Idelisse Malavé: And you were how old then?

Cynthia Madansky: I was 25 and I really loved painting. And I loved being in the studio and I loved the solitary aspects of painting and the depth that you must go with yourself in order to paint. And then at some point, and my film teacher was like, you're going to be a filmmaker. You're going to, I was like, no, I'm not a filmmaker. You know, I like making films, but I'm not a filmmaker. Then I came to New York and went to Cooper Union and I took a video class and I made a film and I went to the Whitney program, but I was like still really attached to it

Idelisse Malavé: What's the Whitney program? a film program?

Cynthia Madansky: No, it's art and you go to a studio and you- I was making work about the first Intifada. I was always a political artist. I- my paintings were always political, not now so much, but now I just do more abstract, but I really came to art from politics and identified as a political artist. And I found that the paintings were not able to articulate what I wanted to say politically. So therefore I went into film. I mean, that's the short answer, but that's when I went into film.

Joanne Sandler: So, one of the things that really brought me together with Cynthia and her old girlfriend, Alisa, was that we had very similar experiences growing up in a middle-class Jewish community in the United States. Right. Where, as Cynthia said, there were basically three things you learned and that whole process for Cynthia. And I think for me, and Alisa as well, of realizing that you were being told a very distorted story and how that really is traumatizing, right? And, and, and also eye opening. And in Cynthia's case how it really became a major theme in her life and a kind of focal point of all of her work, right.

Idelisse Malavé: And how she got politicized, right. And how that shaped and influenced her filmmaking from early films and onwards - through, throughout her career, she shared with us, this is been an important central issue for her

Cynthia Madansky: As nice Jewish girls got reeducated about Zionism. That was our first big reeducation. It was the beginning of Land Day. And there were, it was a much more mixed school in terms of like Palestinians and Jewish Israelis. So, you know, all of a sudden these Jewish girls. So, all of a sudden, these Jewish girls from the suburbs had-

Idelisse Malavé: So, talk a little bit about what that re-education was, what was it before and what did it become?

Cynthia Madansky: Unless you grow up in, as Joanne knows, unless you grow up in a communist socialist Jewish family, you are really brought up on three tenets of Judaism, you know, Jewish culture, religion, Zionism. And if you're Ashkenazi the Holocaust, I mean, I think if you're a, you know, Mizrahi Jewish Sephardic Jewish is different, but as an Ashkenazi Jew, this was the, you know the Bible. So, you know, Zionism was a really big part of our Jewish education.

And, you know, we were brought up on- I'm 58 and it's like, my grandmother escaped the Holocaust. She wasn't in the Holocaust, but people died in the family from the whole, I mean, that's what we were brought up on. So we weren't taught anything about 48 in truth about what happened. And it was all like, you know, the lalala story of yeah.. Jews’ landing in this desert and -

Idelisse Malavé: Exodus, was that the movie?

Cynthia Madansky: yeah.. this is what they still teach a lot of kids and young people. I mean, it's kind of amazing that you go to Hebrew schools today around the country and they're still teaching this language, but of course there's a radical movement right now of young people who are saying, no, we don't accept this as history. And this is not true. And there is

Idelisse Malavé: A lot of displacement of other people..

Cynthia Madansky: but there's a lot of, you know, rupture in that narrative that has been, you know, the hegemonic Zionist narrative.

I think as jews, you have to really look at, I mean, like anybody, you have to look at your racism and you have to really work on. And so, you know, Israel was such a, you know, Zionism was such a like the Jews and suffering and strong and we could do no wrong. And of course, you learn that there was a lot of wrong done.

Treyf is a film I made with an ex-girlfriend who, that's, how I met Joanne, Alisa Lebow. And it was a scripted narrative, basically about being Jewish lesbians. And it was kind of like the first Jewish lesbian identity film that was being made at this time in New York, it was shot in 16 millimeter and we addressed all the issues that we're talking about - 1998, I think we did it-, yeah,

Joanne Sandler: It was such a great film, I loved it so much

Cynthia Madansky: And so, we spoke about, you know, the occupation in the film in a big way, and of course we spoke about other things as well, but that being, you know, Jewish lesbians and blah, blah, blah, but Israel was definitely a big issue - Zionism. And there was a critique of the occupation.

Treyf was in the Jewish film festivals; Still Life has never been in the Jewish film festivals. It's been rejected all the time. And when it was showing at MoMA, they got so many threat letters that they had to have security people there. This is 2003, ḤARĀM, Nobody has been willing to even look at or address. So I don't really know I have to make my work because I have to make my work. And I thought it was an important piece to make, and I hope more people get to see it. And I imagine that I will continue to respond to this occupation. I will continue until the day I die, as a Jewish queer woman to respond to this in as, as an act of resistance. And that it's my obligation and responsibility to articulate this, as long as I'm making work. And if they don't want to see they don't want to see it. But I think that the younger generation will want to see it.

Idelisse Malavé: Cynthia just shared that she makes her work because she has to. And we were able to get into the process by which she makes this work and what shapes this work.

Cynthia Madansky: You know, I'm making interesting avant-garde work. That's in dialogue with what is going on, let's say in the mainstream, but it is avant-garde work and it is not Hollywood and it will never be on net- I mean, some work has been on Sundance channel because there was a very cool curator.

What has to happen is that there's more, you know, radical feminist curators or men. I don't really care about the gender really, or binary or whatever who wants to show, you know, work that challenges also the way of viewing films, because it's not the kind of film with the beginning, middle or end or a narrative. None of my films have that kind of narrative structure. They're not documentaries, they're not narratives that are hybrid in form. So therefore, it's hard to, you know, it's not like, oh, you can just, you know, it's like, here's a character. And I respect filmmakers who make films like that. It's just not the kind of work I make.

Because I'm an artist, and I do so much research and writing, the form really evolves from what I want to articulate. Like I never make the same film again, because I never have the same structure. I never have the same visual language. You could see traits of certain, you know, stamps of my visual language, but ultimately the form really evolves from the material itself. So for instance Esfir, which is my most recent film, which has a re-interpretation of an unrealized script by Esfir Shub called Women, which she wrote in 1933, about the status of women after the revolution, it's a mouthful. I- you know, translated the script from Russian to English, had a translated re-read and re-read, and re-read, and re-read, and re-read it, and then did a contemporary interpretation of it.

So it's not really about Shub, but there's, there's performance in it with a performance, our group in St. Petersburg. And then there were, she, I took the concepts from her script, sex work, motherhood, labor, and the concept of the other. And she wanted to live with four women and make a film about these four women. And then she wrote a script, which was a very different than her original concept. So I kind of did a merging of what her original concept was from her biography plus excerpts from the later script and made a contemporary film about Russian women.

So, I've also been working as a graphic designer to make a living all these years. So, typography, painting, composition are very influential on my filmmaking practice. It's- I see through design and painting and they, I would say those that's politics design and painting really have a big influence on the way I make films and feminism I would say, I would add to it, right?

Idelisse Malavé: So, the whole political as well

Cynthia Madansky: I mean, it's a feminist perspective. This last film was really a feminist horizontally made film where everything was negotiated with these women

Idelisse Malavé: The process you described is very attentive to the emergent, right? You create certain situations or prompts or whatever, and then stuff starts happening. Is that true in your painting as well? Is the help, how present is the emergent in your painting?

Cynthia Madansky: Well, once I stopped making paintings that were about something, and were much more about an internal space and a process, I was free in a certain way. And so, I could just be, I could just go to, I don't know, it sounds so cliche, but I could go to a very deep place in terms of mark making in terms of color, in terms of, you know, fucking up, so to speak. I think when you, when you have a painting, I guess I was, I was able to let go a lot more when I got rid of subject matter. And it gave me space in my head, which I don't have from filmmaking because it's so intellectual. And so research-based, and it's so connected to making sense, even my abstract films have to make more sense than, and they're about something.

Joanne Sandler: So we're talking to Cynthia at the moment where she is returning to New York city now, right. She's been living in St. Petersburg. And I think, as she said in the conversation, she's lived in Jerusalem- Istanbul, Rome.. She comes and goes, right. Which is not a jet-setter lifestyle. Right. Because the question of how you sustain your life as the kind of artists that she is, who is not following conventional lifestyle

Idelisse Malavé: And for whom the Art always comes first

Joanne Sandler: At the Center. Exactly. And so now she talks about a little bit about that. And also now that she's back in the US about pursuing this passion project that she's had on her mind for a long time

Cynthia Madansky: It’s really a dream to get the Guggenheim, it's really an honor to get the Guggenheim. Right.

Idelisse Malavé: And you get recognition as well as some money.

Cynthia Madansky: You know, it's funny, I guess you do get recognition, but I, in this very strange way, I feel like, like some people get recognition and that changes their life. And I feel like, you know, yes, I've been really lucky and you know, to get the grants that I've gotten to get the awards that I've gotten, but, and to make the films that I have been able to make my work is, you know, incredible really, because I know it's not commercial and I know it's political and it's art. And I think the biggest issue is now how to get this work seen, because I'm always working. If I'm not working on my film, I'm working on a job or I'm working on the grant. So I never really do the other piece, which I think artists have to do, which is, you know, meeting people so that you maybe get representation or meeting people so that you get, you know, retrospectives or meeting people that you get this. Or, you know, if somebody is interested in your work and writes about it, it's like I have done nothing on that platform. And partly it's because I'm always working.

I live very minimally and the art comes first, always. I mean, it's always, I breathe it. I live it. And I work at jobs. I mean, I cannot even tell you how many jobs I've done in my life. I mean, you know,

Joanne Sandler: So, you always have a side hustle

Cynthia Madansky: I always, I'm always working. It's like-

Idelisse Malavé: is that as a graphic designer or other things?

Cynthia Madansky: I mean, I'll do many things. I, I like - okay, this last year, all my jobs, well, this last year, this last year I was in Russia and I had a Fulbright. So I didn't actually, I taught- I teach, I taught at Hampshire college for a year as a visiting professor, which I loved. And I taught in Cairo at the American university. I taught at the film school in St. Petersburg. I do workshops with, or I, sometimes I work with young filmmakers who are in works - struggling with works in progress. And so I work with them and mentor them usually for trades, not for money because they have no money- of trades for art. I do graphic design; I consult with artists or curators who need help with writing contracts or for clients. I write reports for people who are doing foundation work. I really, I have done gazillions of jobs and design. Yeah. Whatever comes my way. I'm like, okay. Yeah, I can do this.

I’ve been really lucky with beautiful graphic design jobs. I just designed a book that for a Cuban artist José Angel Toirac, and, you know, I'm very lucky in the beautiful jobs that I get. So, you know, in the scheme of the world and labor issues, I feel, you know, very blessed. And so yes, I would. Would I like more stability? Yes. Would I like to have more grants for my next film and not have to like work so hard to get these grants? but hey, you know, I'll make this film and I will make it -

Cynthia Madansky: I’m not quite sure of the title. The working title is a north American epilogue, and it's basically indexical - an indexical film that will am going to shoot on 16 millimeter that will document every single site and landscape in the United States that has been affected by the nuclear fuel cycle and nuclear industry.

So every state in every all 50 states, and of course just beyond the 50 states have been affected, but I might not get there in this film have been made that- I might not get I'd like to actually, because they have all been affected dramatically, drastically horrendously by the nuclear industry, whether it's milling or mining or nuclear power plants, or contamination or missiles or X plants. And so, I am going to I'm working with a number of nuclear activists around the country, and I want to do oral histories with the older nuclear anti-nuc activists who are now going to pass so that there will be a record of what has been done in each state and each community, and to pass on to the younger generation so they have the information about what has happened here on their landscape. And of course, communities have been documenting it. So it's not, it's just more about creating a hub or a matrix for all of this information across the country. And also, I mean, there are a lot of people who are collecting information. And so I'm hoping that there'll be some kind of database so that everybody would have access to this.

Idelisse Malavé: Right. So that accessibility to it

Cynthia Madansky: So, and then I want to take one roll of film for each location and just make a silent film, almost like Alabama

Idelisse Malavé: for each state or each location,

Cynthia Madansky: for each state, and each state has numerous locations. Son each state, you know, you know, New Mexico probably have the most amount of rolls of film. And also, Idaho and Tennessee, I mean every state is contaminated

I think that this film is really important for climate change because nuclear issues are being omitted from the table and they're not being discussed. And, you know, the fourth level of nuclear reactors are starting to be designed and built and promoted and crazy people like gates are saying, it's clean energy when we know it's not. And this- it's really important. This film is so important on so many levels, not only what I'm shooting, but also the information and the motivation and inserting this nuclear anti-nuc agenda within the climate change. And also within the world peace movement. I mean, this is a feminist, this is, this is on the backs of the feminist anti-nuc movement. That was started all, you know, internationally.

Idelisse Malavé: Cynthia has been making films and painting for more than 40 years of her life. And- and she's a very prolific filmmaker and one has got to wonder: what happens? What do you do with this body of work?

Cynthia Madansky: I have all of my work at the amazing Filmmakers’ Co-op, which is on 30th street, where they have a lot of avant-garde films and 16 millimeter and 35. And it's run by this amazing filmmaker named M.M. Serra, who I love. And so at least I feel like have a home for my archive because I think a lot for artists it's like, where do you leave your work? You know, I don't have any children, you know, my paint is going to go in the garbage, you know, it's like, okay, so at least my films will have a home and will live on at some point because they're relevant in terms of history. And they matter, they matter. And I would like to have screenings and retrospectives, and I would like to design a book and have time to, as a designer, design a book because my, the images of my films are beautiful and the text is really interesting. And so I would like to, you know, have some time and a grant to actually sit and get paid, to have some time to design a book for myself, because I don't have a gallery or somebody who's interested in a book, so I have to- but I might. So that's what I would like to do. I'd like to have a book of my films and I'd like to show my films at retrospectives. And it could be from the MoMA to the Whitney, to, you know, anthology, to grassroots, you know, screening places in, you know, wherever and Mississippi,

Joanne Sandler: If there is one, the message that comes out or is threaded through so many of our conversations on Two Old Bitches, it is this idea- This, I didn't want to call it a regret. It's just this recognition that we all spend way too much time feeling insecure and uncertain about what it was that we wanted to do that we needed to do

Idelisse Malavé: Especially as young women,

Joanne Sandler: Exactly. And as, yeah, as young women, as women. And Cynthia kind of reprises that in her own way, as both a feeling and also advice and then ends up in a much better place.

Cynthia Madansky: I think I was so insecure as a young artist and had to deal with so much, you know, learning how to feel self-worth as an artist and stand behind my work, and every rejection was just like a knife and I would be devastated and I wish I had more support whether it was from, you know- and I, it wasn't that I didn't get support. Of course I did. And I was in again, great schools and, you know, acknowledgement and grants author. But I, I was so insecure as a young woman that I think that's it- I think I would have had a gallery by now if I was not so insecure, like I hide my work. And I think that it's a big problem for a lot of artists. And that's a regret, that I hid my work.